- Lesson Details

- Discussion

- Transcript

- References

- Instructor

- Chris Legaspi, Heather Lenefsky, Mark Westermoe

- Subjects

- Drawing

- Topics

- Light & Color

- Mediums

- Colored Pencil, Pen, Pencil

- Duration

- 4h 23m 33s

- Series

- A Beginner's Guide to Drawing

The New Masters Academy Beginner Series helps aspiring artists start their artistic journey on the right foot. Your expert instructors will gently guide you to an understanding of drawing fundamentals. In this fourth lesson of the series, Chris, Heather, and renowned illustrator Mark Westermoe will show you how to apply the basics using tone, value, and line drawing exercises. You will learn the Laws of Light, rendering techniques, and how to construct basic forms in 3D.

Materials

- Pentel EnerGize Mechanical Pencil

- BIC Cristal Ballpoint Pen – Black

- Staedtler Graphite Pencil

- Conté a Paris Sketching Pencil – Black

- Stabilo CarbOthello Pastel Pencil – Black

- Cretacolor Monolith Woodless Pencil

- Prismacolor Verithin Pencil – Black, White

- Faber-Castell Graphite Pencil

- Uniball Pen

- General Charcoal Pencil

- Tracing Paper

- Bristol Paper

- Sanding Pad

- Toned Paper

- Paintbrush

- Dish Sponge

Beginner Friendly

56759 views

145 likes

Discuss this video in the forums!

DiscussChoose one video.

AUTO SCROLL

The New Masters Academy Beginner Series helps aspiring artists start their artistic journey

on the right foot.

Your expert instructors will gently guide you to an understanding of drawing fundamentals.

In this lesson, Chris and Heather will show you how to apply the basics using tone, value,

and line drawing exercises.

You will then learn the laws of light, rendering techniques,

and how to construct basic forms in 3-D.

on the right foot.

Your expert instructors will gently guide you to an understanding of drawing fundamentals.

In this lesson, Chris and Heather will show you how to apply the basics using tone, value,

and line drawing exercises.

You will then learn the laws of light, rendering techniques,

and how to construct basic forms in 3-D.

AUTO SCROLL

Hey, guys, welcome back.

I’m Chris Legaspi.

And I’m Heather Lenefsky.

In the last lesson, we covered all the fun stuff, all the cool toys artists love; materials,

furniture, pencils, pens, markers, easels, everything you need to get started.

In this lesson, we’re going to show you what to do with all those cool materials.

We’ve got you all hyped up.

And now, the payoff.

You’re going to get to make some marks.

Alright guys, now that you know about the materials and the accessories, let’s talk

about ways that you can use your materials.

We’re going to apply the basics here.

I wanted to start by talking about some exercises that you can do.

I’m going to begin with line drawing exercises.

Line, as we know, is our old friend.

It’ll be the first mark that you make.

It’s kind of like writing, too.

First mark we all make when we pick up pencils and pens.

I’m going to show you a couple of different exercises that you can do to improve your

drawing using line.

So, the first exercise is what I call the connect the dot.

Basically, you just want to put a couple of points on your paper.

One there, one there.

Make it a little darker so you can see it on camera.

Then, voooop, try to connect.

Little off.

Little off.

You don’t have to be perfect.

Now, that was way off.

Oh, my God.

Terrible.

Getting better.

The idea is to practice the motion.

It’s really the motion.

That’s one thing I want to stress, too.

It’s not wrist motion.

You notice I’m not doing….right?

I’m doing this.

You see my whole arm move.

If you see my body you can actually see I’m moving my body too,

especially if you want to get a long line.

So, what I would recommend is to do a whole page, maybe a page in your sketchbook or a

page on like a piece of copy paper and fill it with line.

Draw two dots and try to connect.

As you get more confident you want to get as far as possible.

Let me try a big one. Ready? Here we go.

Ooh, pretty close. Look at that. One more.

One more.

See, this is fun.

Oh, I got it.

Pretty close. That’s the idea.

What I want you guys to do is go in eight directions.

We went left to right.

This is direction one.

Obviously, top to bottom is another one.

Do a whole page of these top to bottom.

And then diagonals.

Go from as long as you want making sure to move your whole body.

You notice that when I move my whole body the line actually becomes a little bit more accurate.

Then to complete the eight directions go in reverse.

This is against what’s naturally comfortable for me, left to right.

You want to do that too.

You’ll want to put yourself in an uncomfortable situation as often as possible because that’ll

really ramp up what is known as dexterity, the ability to hold your tool and make marks

with your tool, dexterity.

So, you’ll want that.

This is kind of awkward for me, but when I go back the other way it’ll be really, really

helpful when I go back the other way.

So, eight different directions: left to right, right to left, top to bottom, bottom to top,

and diagonals going upper left to down, lower left this way, and then in reverse as well.

The next exercise is ellipses and ovals.

Basically, you want to practice drawing curves.

Round forms, curves of various sizes in various shapes and various degrees.

Draw some big ones.

And notice the bigger I get, the more my body is involved.

Again, moving the whole body.

And these, too, you want to go different directions.

Left to right, right to left, diagonals.

And up and down, top to bottom.

What I like about these little exercises is that you can do them almost anywhere, and

you can even draw them if you’re watching your favorite movie or TV show.

Or even when you’re on the phone and you’re on hold on the phone, it’s a great way to

make the most of your time.

Pretty, much when you’re waiting anywhere you can do these wonderful little exercises

to really ramp up your dexterity, your control, and your ability to draw with line.

Let me try and draw a big one.

It’s a lot of fun.

Okay, next thing we’re going to do is a little bit of shading.

I’m going to use a hatching technique.

Hatching is basically shading with line.

I’m going to start with these little squares.

What you want to do is fill the box.

You want a nice, even tone.

Nice even tone.

Do a whole sheet of these boxes,

whole page in your sketch book or a whole sheet of paper. This one is a little off.

What that does is it trains you to do really nice clean and even strokes.

I’m even going to do it with a pen just to show you the importance of line.

What I’m doing here is I’m consciously trying to make my strokes nice and even, nice

and clean so that when you step back the tone reads as a nice, even, uniform, flat tone.

Again, it’s not really about how good the tone looks or how perfect the lines are.

This is really just a mechanical exercise, really muscle memory here.

Of course, you don’t want to go in just your comfortable direction.

For me it was up and down comfortable.

You want to go in four different directions.

Right to left, really make yourself uncomfortable.

Bottom to top.

This one, you notice, is not as clean, so that’s an uncomfortable position for me.

The more I practice that the better my drawing skills will be overall.

Of course, you want to go in diagonals, too.

Nice and even.

Nice and clean.

As best as you can.

Then do the opposite way.

Do these in at least four different directions, filling up squares using hatching, using line

to make nice, even tones.

Okay, the next exercise is similar to the square.

We’re going to fill a rectangle or a bar.

What this does is it’ll help your endurance.

The advantage of making a long bar is that it’ll help with your endurance.

Unlike the small square, the long bar will force you to keep drawing and keep drawing,

and it’ll really improve your muscle memory.

Again, this is a comfortable position for me.

Left to right, bottom to top.

Let’s try the uncomfortable way, another direction.

Oh, my God. I'm straining. Oh, ouch.

It’s like doing push-ups. It’s like doing exercises.

You want to go in, not just horizontal, but vertical rectangles, too.

You want to try and stay as consistent at the bottom as when you get to the top.

That’s going to be tough.

But, that’s what this is for, for really working those muscles, getting that muscle memory.

Again, you can do this almost anywhere in your sketchbook or any sheet of paper.

It’s a great exercise you can take on the road.

Let me try right to left.

Let me try a diagonal and see how that goes.

So, do a whole page of these.

Change up your direction.

Make sure you do half your sheet horizontal and at least half your sheet vertical as well.

Okay, and the final line exercise.

This is going to be the tough one, but I’ve got faith in you guys.

And if you do this, believe me, your drawings will go to the next level.

What we’re going to do is do gradations.

What I’m going to do—instead of doing a bar, I want to do imagining a picture, imagining

like a canvas or a piece of paper.

This is like on my picture, my thumbnail, and I’m going to start doing a gradation

with line in a fairly comfortable direction left to right.

See that?

How it gradates from top to bottom, dark to light.

Let me try the inverse.

It’s another thumbnail.

This would be a cool way to practice doing gradations in skies and things or filling

in the background if you’re going to put a figure or a still life there.

I’m only using line to get a nice gradation.

Notice at the end I leave the white of the paper and reinforce it down here.

Let me try diagonal.

Again, starting with what’s comfortable for me.

Try to make it as smooth as possible using only line.

That one is kind of ugly.

I’ll admit it’s a little ugly.

Let me try this way.

It’s a little better. Nice and smooth.

Let me try it with a pen, too.

With pen I’m going to go in an uncomfortable direction,

which is bottom to top, right to left.

It’s the complete reverse of what’s comfortable for me.

Wish me luck. Here we go.

Ooh, so uncomfortable.

So uncomfortable.

That’s okay, that’s what we want.

This is not a hatching contest by any means.

This isn’t an abstract drawing contest.

This is a pure muscle and draftsmanship exercise.

Draftsmanship is drawing skill.

That was a tough one.

That was a tough one.

Let me try one more tough one just so you know that—oh, let’s try this one.

The inverse diagonal.

Oh, ouch. Ouch.

It’s like doing push-ups.

It’s like doing abdominal crunches.

Oh it hurts.

It hurts.

But you’ll thank yourself later.

Oh, whoo.

My arm is hurting.

Notice I said my arm.

My arm-let me draw a little arm for you- right here is sore, my little shoulder.

I’m drawing from the shoulder.

You notice you don’t see me chicken scratching with what I call these little tiny marks.

No, you want to do umph.

Again, that whole body will help you to make nice and clean marks.

Then we’ll practice your tones.

You’ll get great.

You can see how just these simple exercises alone, even a little bit every day, five or

ten minutes a day, one sheet day, your drawing

and your ability to use your tools will really improve.

So, just a quick review.

Start with line.

Connect the dot exercise, one to another.

Do your best to connect.

Go in at least four different directions.

Go the opposite direction of what’s comfortable to you to really push and strengthen your dexterity

The next series of ellipses and ovals.

Just hand draw ellipses and ovals in multiple directions as well and multiple sizes.

Making sure you use your whole arm, not just your fingers.

Next is filling boxes with only line so use only line to fill a box.

The goal is to make the tone as even as possible.

Make your lines as clean and as even as possible.

The next similar exercise is to do a long bar, a long rectangle to really help your

endurance, your muscle endurance.

Obviously, when you get to the end, you want the end, you’re going to be a little bit

tired, but this is going to really push your endurance.

You want the end to be just as clean and just as useful and just as pretty,

just as even as the beginning.

You want to do these up and down as well.

And finally, the last one.

Instead of trying to do an even tone do a gradation.

Go from dark to light.

I like these little thumbnail, mini picture frame style drawings to kind of help you think

in terms of composition as well while you’re doing your exercises.

You can try them in pen like I’m doing and pencil like I’m doing.

Whatever two you’re comfortable with. I would say try both.

Again, do them as often as you can, even as little as five minutes a day.

Do several pages of practice for the following exercises: Connect the dot exercises in all

eight directions.

Ellipse and oval line exercises in all eight directions.

Shading a square exercise with line in four directions.

Shading a rectangle exercise with line in four directions.

Shading a gradation bar with line in four directions.

There is no limit to how many times you can do these exercises.

Be sure to focus on your weak areas.

I’m Chris Legaspi.

And I’m Heather Lenefsky.

In the last lesson, we covered all the fun stuff, all the cool toys artists love; materials,

furniture, pencils, pens, markers, easels, everything you need to get started.

In this lesson, we’re going to show you what to do with all those cool materials.

We’ve got you all hyped up.

And now, the payoff.

You’re going to get to make some marks.

Alright guys, now that you know about the materials and the accessories, let’s talk

about ways that you can use your materials.

We’re going to apply the basics here.

I wanted to start by talking about some exercises that you can do.

I’m going to begin with line drawing exercises.

Line, as we know, is our old friend.

It’ll be the first mark that you make.

It’s kind of like writing, too.

First mark we all make when we pick up pencils and pens.

I’m going to show you a couple of different exercises that you can do to improve your

drawing using line.

So, the first exercise is what I call the connect the dot.

Basically, you just want to put a couple of points on your paper.

One there, one there.

Make it a little darker so you can see it on camera.

Then, voooop, try to connect.

Little off.

Little off.

You don’t have to be perfect.

Now, that was way off.

Oh, my God.

Terrible.

Getting better.

The idea is to practice the motion.

It’s really the motion.

That’s one thing I want to stress, too.

It’s not wrist motion.

You notice I’m not doing….right?

I’m doing this.

You see my whole arm move.

If you see my body you can actually see I’m moving my body too,

especially if you want to get a long line.

So, what I would recommend is to do a whole page, maybe a page in your sketchbook or a

page on like a piece of copy paper and fill it with line.

Draw two dots and try to connect.

As you get more confident you want to get as far as possible.

Let me try a big one. Ready? Here we go.

Ooh, pretty close. Look at that. One more.

One more.

See, this is fun.

Oh, I got it.

Pretty close. That’s the idea.

What I want you guys to do is go in eight directions.

We went left to right.

This is direction one.

Obviously, top to bottom is another one.

Do a whole page of these top to bottom.

And then diagonals.

Go from as long as you want making sure to move your whole body.

You notice that when I move my whole body the line actually becomes a little bit more accurate.

Then to complete the eight directions go in reverse.

This is against what’s naturally comfortable for me, left to right.

You want to do that too.

You’ll want to put yourself in an uncomfortable situation as often as possible because that’ll

really ramp up what is known as dexterity, the ability to hold your tool and make marks

with your tool, dexterity.

So, you’ll want that.

This is kind of awkward for me, but when I go back the other way it’ll be really, really

helpful when I go back the other way.

So, eight different directions: left to right, right to left, top to bottom, bottom to top,

and diagonals going upper left to down, lower left this way, and then in reverse as well.

The next exercise is ellipses and ovals.

Basically, you want to practice drawing curves.

Round forms, curves of various sizes in various shapes and various degrees.

Draw some big ones.

And notice the bigger I get, the more my body is involved.

Again, moving the whole body.

And these, too, you want to go different directions.

Left to right, right to left, diagonals.

And up and down, top to bottom.

What I like about these little exercises is that you can do them almost anywhere, and

you can even draw them if you’re watching your favorite movie or TV show.

Or even when you’re on the phone and you’re on hold on the phone, it’s a great way to

make the most of your time.

Pretty, much when you’re waiting anywhere you can do these wonderful little exercises

to really ramp up your dexterity, your control, and your ability to draw with line.

Let me try and draw a big one.

It’s a lot of fun.

Okay, next thing we’re going to do is a little bit of shading.

I’m going to use a hatching technique.

Hatching is basically shading with line.

I’m going to start with these little squares.

What you want to do is fill the box.

You want a nice, even tone.

Nice even tone.

Do a whole sheet of these boxes,

whole page in your sketch book or a whole sheet of paper. This one is a little off.

What that does is it trains you to do really nice clean and even strokes.

I’m even going to do it with a pen just to show you the importance of line.

What I’m doing here is I’m consciously trying to make my strokes nice and even, nice

and clean so that when you step back the tone reads as a nice, even, uniform, flat tone.

Again, it’s not really about how good the tone looks or how perfect the lines are.

This is really just a mechanical exercise, really muscle memory here.

Of course, you don’t want to go in just your comfortable direction.

For me it was up and down comfortable.

You want to go in four different directions.

Right to left, really make yourself uncomfortable.

Bottom to top.

This one, you notice, is not as clean, so that’s an uncomfortable position for me.

The more I practice that the better my drawing skills will be overall.

Of course, you want to go in diagonals, too.

Nice and even.

Nice and clean.

As best as you can.

Then do the opposite way.

Do these in at least four different directions, filling up squares using hatching, using line

to make nice, even tones.

Okay, the next exercise is similar to the square.

We’re going to fill a rectangle or a bar.

What this does is it’ll help your endurance.

The advantage of making a long bar is that it’ll help with your endurance.

Unlike the small square, the long bar will force you to keep drawing and keep drawing,

and it’ll really improve your muscle memory.

Again, this is a comfortable position for me.

Left to right, bottom to top.

Let’s try the uncomfortable way, another direction.

Oh, my God. I'm straining. Oh, ouch.

It’s like doing push-ups. It’s like doing exercises.

You want to go in, not just horizontal, but vertical rectangles, too.

You want to try and stay as consistent at the bottom as when you get to the top.

That’s going to be tough.

But, that’s what this is for, for really working those muscles, getting that muscle memory.

Again, you can do this almost anywhere in your sketchbook or any sheet of paper.

It’s a great exercise you can take on the road.

Let me try right to left.

Let me try a diagonal and see how that goes.

So, do a whole page of these.

Change up your direction.

Make sure you do half your sheet horizontal and at least half your sheet vertical as well.

Okay, and the final line exercise.

This is going to be the tough one, but I’ve got faith in you guys.

And if you do this, believe me, your drawings will go to the next level.

What we’re going to do is do gradations.

What I’m going to do—instead of doing a bar, I want to do imagining a picture, imagining

like a canvas or a piece of paper.

This is like on my picture, my thumbnail, and I’m going to start doing a gradation

with line in a fairly comfortable direction left to right.

See that?

How it gradates from top to bottom, dark to light.

Let me try the inverse.

It’s another thumbnail.

This would be a cool way to practice doing gradations in skies and things or filling

in the background if you’re going to put a figure or a still life there.

I’m only using line to get a nice gradation.

Notice at the end I leave the white of the paper and reinforce it down here.

Let me try diagonal.

Again, starting with what’s comfortable for me.

Try to make it as smooth as possible using only line.

That one is kind of ugly.

I’ll admit it’s a little ugly.

Let me try this way.

It’s a little better. Nice and smooth.

Let me try it with a pen, too.

With pen I’m going to go in an uncomfortable direction,

which is bottom to top, right to left.

It’s the complete reverse of what’s comfortable for me.

Wish me luck. Here we go.

Ooh, so uncomfortable.

So uncomfortable.

That’s okay, that’s what we want.

This is not a hatching contest by any means.

This isn’t an abstract drawing contest.

This is a pure muscle and draftsmanship exercise.

Draftsmanship is drawing skill.

That was a tough one.

That was a tough one.

Let me try one more tough one just so you know that—oh, let’s try this one.

The inverse diagonal.

Oh, ouch. Ouch.

It’s like doing push-ups.

It’s like doing abdominal crunches.

Oh it hurts.

It hurts.

But you’ll thank yourself later.

Oh, whoo.

My arm is hurting.

Notice I said my arm.

My arm-let me draw a little arm for you- right here is sore, my little shoulder.

I’m drawing from the shoulder.

You notice you don’t see me chicken scratching with what I call these little tiny marks.

No, you want to do umph.

Again, that whole body will help you to make nice and clean marks.

Then we’ll practice your tones.

You’ll get great.

You can see how just these simple exercises alone, even a little bit every day, five or

ten minutes a day, one sheet day, your drawing

and your ability to use your tools will really improve.

So, just a quick review.

Start with line.

Connect the dot exercise, one to another.

Do your best to connect.

Go in at least four different directions.

Go the opposite direction of what’s comfortable to you to really push and strengthen your dexterity

The next series of ellipses and ovals.

Just hand draw ellipses and ovals in multiple directions as well and multiple sizes.

Making sure you use your whole arm, not just your fingers.

Next is filling boxes with only line so use only line to fill a box.

The goal is to make the tone as even as possible.

Make your lines as clean and as even as possible.

The next similar exercise is to do a long bar, a long rectangle to really help your

endurance, your muscle endurance.

Obviously, when you get to the end, you want the end, you’re going to be a little bit

tired, but this is going to really push your endurance.

You want the end to be just as clean and just as useful and just as pretty,

just as even as the beginning.

You want to do these up and down as well.

And finally, the last one.

Instead of trying to do an even tone do a gradation.

Go from dark to light.

I like these little thumbnail, mini picture frame style drawings to kind of help you think

in terms of composition as well while you’re doing your exercises.

You can try them in pen like I’m doing and pencil like I’m doing.

Whatever two you’re comfortable with. I would say try both.

Again, do them as often as you can, even as little as five minutes a day.

Do several pages of practice for the following exercises: Connect the dot exercises in all

eight directions.

Ellipse and oval line exercises in all eight directions.

Shading a square exercise with line in four directions.

Shading a rectangle exercise with line in four directions.

Shading a gradation bar with line in four directions.

There is no limit to how many times you can do these exercises.

Be sure to focus on your weak areas.

AUTO SCROLL

Alright, now we’ve covered some linear exercises using line,

and we’re going to move on to tone.

You guys, these are super important lessons, and they’ll really help you to draw better

and improve your overall skills.

So, let’s get started.

Let’s imagine we want to look at a five value range from light to dark.

And since we always want to practice kind of seeing things in the thumbnail if possible,

let’s go ahead and do it in a series of boxes rather than just a strip.

We’re going to do five little puddles here.

I’m just using a Conté.

I’m going to get some kind of boxy looking shapes.

Let’s put a fifth one in here.

The cool thing is, this one is going to be the white of the canvas or the paper.

That one is done. Check.

And so I think a good way to kind of approach it would be—you know, maybe we’ll look

first at the darkest dark and the lightest light.

I’m going to use the edge of the Conté because when we’re doing tone we’re flipping

it to that thick side.

You know, Chris really was working out there doing all those lines.

I feel like this is cheating.

I’m just trying to get a smooth tone.

I’m going to build up kind of slowly.

When you go slower you can be more conscientious of your pressure that you’re using.

That way you can keep it smooth versus if I get really dark really fast here, you know,

I might not be able to quite match it up without getting some kind of line in between.

If you can kind of smoothly that’s also a nice tool to be able to develop.

I used to just draw Tetris shapes on my pad to warm up kind of a fun variation on a theme.

We get this one pretty dark.

I’m starting to press into the grain of the paper.

Let’s see if that can be our darkest dark.

Let’s kind of estimate maybe what 50% is between the darkest dark

and the lightest light here.

Again, kind of uniform, trying to be clean so that it’s kind of uniform.

I’m going to come back across again.

I’m doing this the easy way for me, so gravity is being kind of useful on this table.

I’m just sort of letting it fall.

Alright, let’s see.

That might even be getting dark there.

One thing we might do is just lift a little bit out, kind of blend it in a little bit.

Let’s see if this kind of—just to kind of get it looking nice.

We’ve just got the tissue there.

And I still think that’s a little dark probably.

And so, with drawing and with art, you want to sneak up on something slowly so you don’t

overshoot your mark.

A lot of times it’s like a pendulum.

You go, well, shoot, I pushed that a little darker than maybe I ought to have, so let’s

see if I can make this a little darker to compensate.

That looks a little better.

We might have to come up a little lighter on that.

Maybe I’ll pick off a little bit.

But, for now let’s see if, you know, let’s look at the lightest light here and see what

this looks like.

And this paper is going to pick it up quick, so I’m going to try to be much more careful.

We look and we go does that look like 50%?

No, that’s more close to the light to the middle here.

Let’s take another pass at it.

That’s kind of how this goes.

You make a choice and you stop and you go is that right.

Kind of evaluate and go back in.

It’s really not magic.

It’s just a series of decisions.

When you get better at making decisions and your hand gets better at performing them,

your stuff starts to look better.

We’re getting warmer.

Let’s put this one in and see what we think.

Just kind of following that same stroke to lay the tone in.

Now, if I stop here, that’s not nearly enough.

I’m going to start leaning on it a little more.

Kind of rotate it in my hand to keep that tip looking nice instead of starting to get

a flat edge on it.

Alright, let’s give it the Kleenex treatment.

Let’s see what this does.

Let’s see if we’re getting any warmer.

Alright, what do you think?

So, this kinda still, this is really close to this, and this is really close to this.

We might want to see if we can just draw a little more distinction between these.

But, this is the idea, and so as you get a feel for your paper and you get a feel for

your instrument, you’re going to go back and forth, and you’re going to try to really

pay attention and study value.

You know, it seems like filing in a couple of boxes would be a piece of cake, but most

of these things they do require—I mean all of it, the more present you can be, the more

seriously you can kind of take it, it’s just good to start cultivating it now even

though we’re little coloring in boxes.

So, you kind of get the idea.

Once you start to play with the five values then we’re going to look at something similar,

but we’re going to limit the range of values to a high key or a low key.

Before we do that, though, I’m going to go ahead and just mark a little shapes in here.

Let’s work on just some gradients.

Maybe full dark to light here.

So, let’s do one of these maybe here from side to side, kind of follow that last.

I’m just using sort of a generic shape here because if we’re really going to be doing

thumbnails down the road, as far as making pictures go,

that rectangle can kind of come in handy.

Now within just one shape, same idea, we’re just going to see if we can slowly build tone.

I’ve got my knuckles here resting down.

Again, if you can see this wrist is pretty locked out.

My shoulders aren’t as strong as Chris’, but I’m working on it.

It really is, it’s something you’re doing with your body.

You’re not up on it from the wrist here.

We’re pulling down from deeper back up here towards the shoulder.

So, just something like that.

Using the shoulder.

I got my core activated.

I’m not joking around.

Something like that.

Then maybe we say, well, do we keep the light in there?

You know, come back in, draw with the eraser a little bit.

We’ve got, you know, sweaty Kleenex here.

The stump, the eraser, you can bring all these guys out.

Let’s see, should I grab something else?

Let’s try it with this little guy, a little charcoal.

See what kind of trouble we can get in.

I’m going to draw one more of these shapes.

We’ll say something like that.

It could be a portrait.

It could be whatever.

We’re going to go full value, let’s say on a diagonal.

Laying in a gradient is really important.

The light is never going to hit an object the same the whole way across it.

You’ll start noticing this the more you observe.

And so practicing laying in a gradient,

I mean you’re going to laying in gradients for everything.

We’re going to get a little bit of tone, kind of feather it down, get your finger up.

Fingers are fun.

Too far down there.

Then we’ll start to lay in towards this corner.

You can get your finger in there, start to get something like that.

If you can step back and look, say dark, light, and then see if the middle strip looks like 50%.

Maybe it’s too light.

Maybe we just want to put a little more.

Remember to step back and check.

It’s like a puzzle.

Did we get it?

It looks a little better.

Maybe something like that.

We’ve been looking at dark to light using kind of like a full scale.

If we numbered these, maybe this goes all the way from ten to one or one to ten depending

on how you like to think of it.

Let’s look at just using one portion.

We can shift to either end of the spectrum and stay within the darks or within the lights.

We don’t need to use every single one of these ranges.

That’s talking about high key versus low key.

So, let’s do another one here.

Let’s start with the mostly light.

We’ll keep that—maybe we’ll do a horizontal one there.

Alright.

If we’re staying mostly light, our darkest dark is going to be maybe closer to like a

midrange thing.

I almost wanted to go back in there and fix it again.

See, this is what happens.

You’re never done.

You just have to put stuff away sometimes.

Let’s see if we can lay the darkest dark in it, 50%.

This paper is going to take this up.

It’s really going to be useful having.

Hopefully that Kleenex dried it out.

Let’s try it.

If we’re staying in high key we really don’t want to get it too, too dark.

Like a rub-in.

Okay, so we know we want this to be the tone of the paper, so we don’t want to get too

carried away yet.

Okay, let’s step back.

How are we looking on the gray?

It’s roughly 50%.

You guys will give it to me, right?

Alright, so we’ll lay in a little more, but we want it to hit white by the end here.

This middle range, we’ve got to be careful with it.

I’ve barely put too much tone on there.

I’m kind of just hoping with these accessories I can pull that tone across.

I don’t think I can make a mark that light.

Maybe if I was really good.

I mean, it’s hard.

It’s a lot harder.

You can think about the tools you’re using and say, well, let’s get an assist with

something like this.

That can really help.

So, something like that might be closer to a narrow range of value in a higher key.

Okay, let’s look at pushing it to the lower side.

This one might be a little easier.

It’s probably a little more easily forgiven.

Just getting crazy lay-in tone on dark.

Although, you’ve got to be pretty sure if you’re drawing and you’re just leaning

on it like this.

But, for this exercise we know this needs to be dark.

We’re going to put it in.

Also, this is easier to smear.

This one is going to sit more on top of that paper.

I’m not as worried about laying it in.

With this Conté, you know it seems like it can scratch the paper.

It can leave more of a delineation between strokes.

This one I think is probably more forgiving.

Alright, so we know we want the darkest dark.

What do we want the lightest light to be?

We’re going to go back.

We’re going to say maybe the middle, that middle gray.

Where this one started, that’s kind of where we want this one to end.

Let’s just see if we can get something close to that mid five on the ten to one scale.

I’m just kind of leaving more space in between the paper because the pressure of this, you

know, it kind of feels like all or nothing sometimes.

So, grabbing another tool.

See if I can.

Alright, so what do we think?

It’s kind of light maybe.

Maybe we can push it a little darker.

I like getting these ends in because then you have something to judge.

If I just started here and, I mean, I don’t know where it’s going to end up.

This is telling me, this is your start point, this is your end point, and then fill in the

middle.

You know, it’s like if you were going to draw an arm, you probably would want to estimate

at some point how long the arm was before you just started drawing all the little anatomy

along the way.

It’s kind of nice to know where something ends.

Kind of mark that.

Okay, so now if we decide we’re cool with this being the end point, now let’s make

this gradate into that.

We need a little more.

It’s just step by step.

A lot of little steps.

Do something, think about it.

Do something, think about it.

Alright.

Get the finger going.

Okay, what do you think?

Pretty close.

Maybe we can get some better kind of distinction there.

That’s about as dark as this can go.

I might want that to read a little bit lighter at the end.

Even when I’m doing this I’m totally moving my whole arm.

I love that I get to stand up and do this too.

That kind of gets you in the mood.

I think it’s easier to get in those traps of moving just your wrist when you’re sitting.

When you’re standing up it’s a little easier to remember you’re using your whole body.

So, something like that, maybe.

It’s pretty close.

So, you get the idea.

Just think about the way you’re laying it down.

Think about how you’re going to make those decisions.

I still keep wanting to go back and fix this, and that’s okay.

You can spend some time trying to get it right.

Just remember how much work it takes to do a good job and know that it’s supposed to.

The longer your work on this stuff, the faster you’ll get at it.

It always takes your presence.

and we’re going to move on to tone.

You guys, these are super important lessons, and they’ll really help you to draw better

and improve your overall skills.

So, let’s get started.

Let’s imagine we want to look at a five value range from light to dark.

And since we always want to practice kind of seeing things in the thumbnail if possible,

let’s go ahead and do it in a series of boxes rather than just a strip.

We’re going to do five little puddles here.

I’m just using a Conté.

I’m going to get some kind of boxy looking shapes.

Let’s put a fifth one in here.

The cool thing is, this one is going to be the white of the canvas or the paper.

That one is done. Check.

And so I think a good way to kind of approach it would be—you know, maybe we’ll look

first at the darkest dark and the lightest light.

I’m going to use the edge of the Conté because when we’re doing tone we’re flipping

it to that thick side.

You know, Chris really was working out there doing all those lines.

I feel like this is cheating.

I’m just trying to get a smooth tone.

I’m going to build up kind of slowly.

When you go slower you can be more conscientious of your pressure that you’re using.

That way you can keep it smooth versus if I get really dark really fast here, you know,

I might not be able to quite match it up without getting some kind of line in between.

If you can kind of smoothly that’s also a nice tool to be able to develop.

I used to just draw Tetris shapes on my pad to warm up kind of a fun variation on a theme.

We get this one pretty dark.

I’m starting to press into the grain of the paper.

Let’s see if that can be our darkest dark.

Let’s kind of estimate maybe what 50% is between the darkest dark

and the lightest light here.

Again, kind of uniform, trying to be clean so that it’s kind of uniform.

I’m going to come back across again.

I’m doing this the easy way for me, so gravity is being kind of useful on this table.

I’m just sort of letting it fall.

Alright, let’s see.

That might even be getting dark there.

One thing we might do is just lift a little bit out, kind of blend it in a little bit.

Let’s see if this kind of—just to kind of get it looking nice.

We’ve just got the tissue there.

And I still think that’s a little dark probably.

And so, with drawing and with art, you want to sneak up on something slowly so you don’t

overshoot your mark.

A lot of times it’s like a pendulum.

You go, well, shoot, I pushed that a little darker than maybe I ought to have, so let’s

see if I can make this a little darker to compensate.

That looks a little better.

We might have to come up a little lighter on that.

Maybe I’ll pick off a little bit.

But, for now let’s see if, you know, let’s look at the lightest light here and see what

this looks like.

And this paper is going to pick it up quick, so I’m going to try to be much more careful.

We look and we go does that look like 50%?

No, that’s more close to the light to the middle here.

Let’s take another pass at it.

That’s kind of how this goes.

You make a choice and you stop and you go is that right.

Kind of evaluate and go back in.

It’s really not magic.

It’s just a series of decisions.

When you get better at making decisions and your hand gets better at performing them,

your stuff starts to look better.

We’re getting warmer.

Let’s put this one in and see what we think.

Just kind of following that same stroke to lay the tone in.

Now, if I stop here, that’s not nearly enough.

I’m going to start leaning on it a little more.

Kind of rotate it in my hand to keep that tip looking nice instead of starting to get

a flat edge on it.

Alright, let’s give it the Kleenex treatment.

Let’s see what this does.

Let’s see if we’re getting any warmer.

Alright, what do you think?

So, this kinda still, this is really close to this, and this is really close to this.

We might want to see if we can just draw a little more distinction between these.

But, this is the idea, and so as you get a feel for your paper and you get a feel for

your instrument, you’re going to go back and forth, and you’re going to try to really

pay attention and study value.

You know, it seems like filing in a couple of boxes would be a piece of cake, but most

of these things they do require—I mean all of it, the more present you can be, the more

seriously you can kind of take it, it’s just good to start cultivating it now even

though we’re little coloring in boxes.

So, you kind of get the idea.

Once you start to play with the five values then we’re going to look at something similar,

but we’re going to limit the range of values to a high key or a low key.

Before we do that, though, I’m going to go ahead and just mark a little shapes in here.

Let’s work on just some gradients.

Maybe full dark to light here.

So, let’s do one of these maybe here from side to side, kind of follow that last.

I’m just using sort of a generic shape here because if we’re really going to be doing

thumbnails down the road, as far as making pictures go,

that rectangle can kind of come in handy.

Now within just one shape, same idea, we’re just going to see if we can slowly build tone.

I’ve got my knuckles here resting down.

Again, if you can see this wrist is pretty locked out.

My shoulders aren’t as strong as Chris’, but I’m working on it.

It really is, it’s something you’re doing with your body.

You’re not up on it from the wrist here.

We’re pulling down from deeper back up here towards the shoulder.

So, just something like that.

Using the shoulder.

I got my core activated.

I’m not joking around.

Something like that.

Then maybe we say, well, do we keep the light in there?

You know, come back in, draw with the eraser a little bit.

We’ve got, you know, sweaty Kleenex here.

The stump, the eraser, you can bring all these guys out.

Let’s see, should I grab something else?

Let’s try it with this little guy, a little charcoal.

See what kind of trouble we can get in.

I’m going to draw one more of these shapes.

We’ll say something like that.

It could be a portrait.

It could be whatever.

We’re going to go full value, let’s say on a diagonal.

Laying in a gradient is really important.

The light is never going to hit an object the same the whole way across it.

You’ll start noticing this the more you observe.

And so practicing laying in a gradient,

I mean you’re going to laying in gradients for everything.

We’re going to get a little bit of tone, kind of feather it down, get your finger up.

Fingers are fun.

Too far down there.

Then we’ll start to lay in towards this corner.

You can get your finger in there, start to get something like that.

If you can step back and look, say dark, light, and then see if the middle strip looks like 50%.

Maybe it’s too light.

Maybe we just want to put a little more.

Remember to step back and check.

It’s like a puzzle.

Did we get it?

It looks a little better.

Maybe something like that.

We’ve been looking at dark to light using kind of like a full scale.

If we numbered these, maybe this goes all the way from ten to one or one to ten depending

on how you like to think of it.

Let’s look at just using one portion.

We can shift to either end of the spectrum and stay within the darks or within the lights.

We don’t need to use every single one of these ranges.

That’s talking about high key versus low key.

So, let’s do another one here.

Let’s start with the mostly light.

We’ll keep that—maybe we’ll do a horizontal one there.

Alright.

If we’re staying mostly light, our darkest dark is going to be maybe closer to like a

midrange thing.

I almost wanted to go back in there and fix it again.

See, this is what happens.

You’re never done.

You just have to put stuff away sometimes.

Let’s see if we can lay the darkest dark in it, 50%.

This paper is going to take this up.

It’s really going to be useful having.

Hopefully that Kleenex dried it out.

Let’s try it.

If we’re staying in high key we really don’t want to get it too, too dark.

Like a rub-in.

Okay, so we know we want this to be the tone of the paper, so we don’t want to get too

carried away yet.

Okay, let’s step back.

How are we looking on the gray?

It’s roughly 50%.

You guys will give it to me, right?

Alright, so we’ll lay in a little more, but we want it to hit white by the end here.

This middle range, we’ve got to be careful with it.

I’ve barely put too much tone on there.

I’m kind of just hoping with these accessories I can pull that tone across.

I don’t think I can make a mark that light.

Maybe if I was really good.

I mean, it’s hard.

It’s a lot harder.

You can think about the tools you’re using and say, well, let’s get an assist with

something like this.

That can really help.

So, something like that might be closer to a narrow range of value in a higher key.

Okay, let’s look at pushing it to the lower side.

This one might be a little easier.

It’s probably a little more easily forgiven.

Just getting crazy lay-in tone on dark.

Although, you’ve got to be pretty sure if you’re drawing and you’re just leaning

on it like this.

But, for this exercise we know this needs to be dark.

We’re going to put it in.

Also, this is easier to smear.

This one is going to sit more on top of that paper.

I’m not as worried about laying it in.

With this Conté, you know it seems like it can scratch the paper.

It can leave more of a delineation between strokes.

This one I think is probably more forgiving.

Alright, so we know we want the darkest dark.

What do we want the lightest light to be?

We’re going to go back.

We’re going to say maybe the middle, that middle gray.

Where this one started, that’s kind of where we want this one to end.

Let’s just see if we can get something close to that mid five on the ten to one scale.

I’m just kind of leaving more space in between the paper because the pressure of this, you

know, it kind of feels like all or nothing sometimes.

So, grabbing another tool.

See if I can.

Alright, so what do we think?

It’s kind of light maybe.

Maybe we can push it a little darker.

I like getting these ends in because then you have something to judge.

If I just started here and, I mean, I don’t know where it’s going to end up.

This is telling me, this is your start point, this is your end point, and then fill in the

middle.

You know, it’s like if you were going to draw an arm, you probably would want to estimate

at some point how long the arm was before you just started drawing all the little anatomy

along the way.

It’s kind of nice to know where something ends.

Kind of mark that.

Okay, so now if we decide we’re cool with this being the end point, now let’s make

this gradate into that.

We need a little more.

It’s just step by step.

A lot of little steps.

Do something, think about it.

Do something, think about it.

Alright.

Get the finger going.

Okay, what do you think?

Pretty close.

Maybe we can get some better kind of distinction there.

That’s about as dark as this can go.

I might want that to read a little bit lighter at the end.

Even when I’m doing this I’m totally moving my whole arm.

I love that I get to stand up and do this too.

That kind of gets you in the mood.

I think it’s easier to get in those traps of moving just your wrist when you’re sitting.

When you’re standing up it’s a little easier to remember you’re using your whole body.

So, something like that, maybe.

It’s pretty close.

So, you get the idea.

Just think about the way you’re laying it down.

Think about how you’re going to make those decisions.

I still keep wanting to go back and fix this, and that’s okay.

You can spend some time trying to get it right.

Just remember how much work it takes to do a good job and know that it’s supposed to.

The longer your work on this stuff, the faster you’ll get at it.

It always takes your presence.

AUTO SCROLL

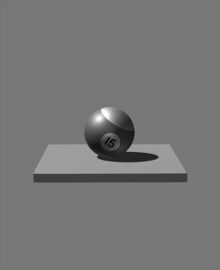

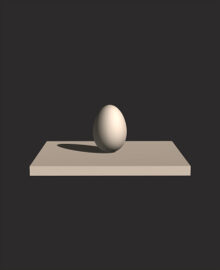

Okay, here we have our basic forms in 3-D form.

This is actual 3-D.

We live in a 3-D world but our medium is flat.

Our drawing paper is flat.

The goal is to get our drawings to feel like these guys.

One of the ways we do that is to not only draw in 3-D but to think in 3-D, and part

of that is not only looking at the edges or the sides but also the backside, the underside,

the part you can’t see.

That’s the goal here, and that’s what we’ll be able to do in this lesson with

these drawing techniques, being able to draw through.

Also, the advantage of form drawing, 3-D drawing, we’ll be able to draw from imagination.

We can take these forms and draw them from almost any angle from imagination left to

right, top to bottom.

Like with the cube, also with the cylinder we're able to draw it

from any angle from imagination.

We’ll also make our forms feel like they’re coming at us.

You see that?

Normally when you think of cylinder you just think of one face.

Maybe you can see a little bit of the top or a little bit of the bottom, but we also

want to be able to do this.

And that’s cool.

That’s cool to make it feel like it’s coming at you or make it feel like it’s

going away from you as well.

The sphere, obviously from any angle, from every angle that you look at, the perfect

sphere, the shape will be the same, the outer edge will be the same.

But, I’ll show you some ways that you can make that feel more 3-D.

The thing that’s important about these is we’re not just drawing boxes and cylinders

and spheres, of course, we want to be able to combine these to create more complex forms.

These will eventually become the complex forms we all want to draw.

Simple objects, still-life objects, even landscapes and obviously and organic things like people, animals.

If you think about it, the human body can be broken down into these basic forms.

That’s what we’re going to focus on in this lesson.

How to be able to think in 3-D. Think of not just the front, but the back.

Not just the top but the bottom parts that you can’t see, and also be able to draw

in 3-D. Draw through the form.

Imagine that these are transparent things.

You can’t see through them, but in our mind’s eye we will be able to think transparently

and be able to draw even the parts we can’t see, and show the audience that our drawing

is just as real, and 2-D space can feel just as real as the real thing.

One of the ways we’ll be able to get the illusion of the form to make it look 3-D is

we’re going to be using perspective.

Now, you may be familiar with some concepts of perspective, and one of the major ideas

in perspective that’s very important that we’re going to be using in this lesson is

what’s known as the horizon line.

The horizon line is the imaginary line.

It means literally, you can think of it as the horizon on the earth when you’re looking

out into a landscape.

You can see that long, horizontal line.

What we want to do when we draw is we want to use what’s called the eyeline.

The difference between the horizon line and the eyeline is that the eyeline is really

where you are looking and also where your audience will be looking.

When I’ll be drawing in this lesson, when I mention the lesson, when I mention the eyeline.

One of the ways you can think about it to help you find the eyeline is by using a pencil

or anything you like to draw with and just put it right in front of your eyes.

This is my eyeline, really.

Also, your viewer’s eyeline, the audience, the people looking at our drawings.

And so, no the matter where you look, if you put the pencil directly in front of your eyes,

this becomes your eyeline.

You can even tilt your head.

When I talk about eyeline, this is what I’m referring to.

It’s not the horizon line, although the same principles and ideas of perspective,

the vanishing points and things, the converging lines apply to the eyeline, but for us, for

artists when we’re doing our 3-D form drawings, this is the one we want to focus on.

Not the horizon line, but the eyeline or the view from your eyes or the from the audience.

This is actual 3-D.

We live in a 3-D world but our medium is flat.

Our drawing paper is flat.

The goal is to get our drawings to feel like these guys.

One of the ways we do that is to not only draw in 3-D but to think in 3-D, and part

of that is not only looking at the edges or the sides but also the backside, the underside,

the part you can’t see.

That’s the goal here, and that’s what we’ll be able to do in this lesson with

these drawing techniques, being able to draw through.

Also, the advantage of form drawing, 3-D drawing, we’ll be able to draw from imagination.

We can take these forms and draw them from almost any angle from imagination left to

right, top to bottom.

Like with the cube, also with the cylinder we're able to draw it

from any angle from imagination.

We’ll also make our forms feel like they’re coming at us.

You see that?

Normally when you think of cylinder you just think of one face.

Maybe you can see a little bit of the top or a little bit of the bottom, but we also

want to be able to do this.

And that’s cool.

That’s cool to make it feel like it’s coming at you or make it feel like it’s

going away from you as well.

The sphere, obviously from any angle, from every angle that you look at, the perfect

sphere, the shape will be the same, the outer edge will be the same.

But, I’ll show you some ways that you can make that feel more 3-D.

The thing that’s important about these is we’re not just drawing boxes and cylinders

and spheres, of course, we want to be able to combine these to create more complex forms.

These will eventually become the complex forms we all want to draw.

Simple objects, still-life objects, even landscapes and obviously and organic things like people, animals.

If you think about it, the human body can be broken down into these basic forms.

That’s what we’re going to focus on in this lesson.

How to be able to think in 3-D. Think of not just the front, but the back.

Not just the top but the bottom parts that you can’t see, and also be able to draw

in 3-D. Draw through the form.

Imagine that these are transparent things.

You can’t see through them, but in our mind’s eye we will be able to think transparently

and be able to draw even the parts we can’t see, and show the audience that our drawing

is just as real, and 2-D space can feel just as real as the real thing.

One of the ways we’ll be able to get the illusion of the form to make it look 3-D is

we’re going to be using perspective.

Now, you may be familiar with some concepts of perspective, and one of the major ideas

in perspective that’s very important that we’re going to be using in this lesson is

what’s known as the horizon line.

The horizon line is the imaginary line.

It means literally, you can think of it as the horizon on the earth when you’re looking

out into a landscape.

You can see that long, horizontal line.

What we want to do when we draw is we want to use what’s called the eyeline.

The difference between the horizon line and the eyeline is that the eyeline is really

where you are looking and also where your audience will be looking.

When I’ll be drawing in this lesson, when I mention the lesson, when I mention the eyeline.

One of the ways you can think about it to help you find the eyeline is by using a pencil

or anything you like to draw with and just put it right in front of your eyes.

This is my eyeline, really.

Also, your viewer’s eyeline, the audience, the people looking at our drawings.

And so, no the matter where you look, if you put the pencil directly in front of your eyes,

this becomes your eyeline.

You can even tilt your head.

When I talk about eyeline, this is what I’m referring to.

It’s not the horizon line, although the same principles and ideas of perspective,

the vanishing points and things, the converging lines apply to the eyeline, but for us, for

artists when we’re doing our 3-D form drawings, this is the one we want to focus on.

Not the horizon line, but the eyeline or the view from your eyes or the from the audience.

AUTO SCROLL

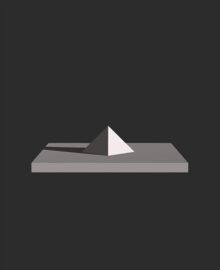

Okay, let's begin with shape basically you want to think of it

as the 2D, the silhouette, also known as the contour.

Other ways you can think about it, shape,

contour,

silhouette. French word.

Basically means the outer edge

and we're going to start with our basic forms.

In this case as a shape it is a circle and notice the way I'm

drawing again, drawing with the whole body, drawing through,

practicing, ghosting, before I commit to a line.

Really helps to make better circles and to make our forms

feel more 3D and real that's the end goal. Next is the cube,

the box.

And the outer edge of the box,

contour, silhouette very simple.

If we just look at the box itself the contour in this form

in this flat 2D graphic shape, silhouette of the box, the outer

edge almost appears like another shape,

hexagon shape, notice that. And then finally the cylinder.

Cylinder,

interesting shape.

It's basically like the box here but curved at the end.

So very simple, very graphic.

Okay. Next we're going to do the 3D drawing, starting with

the box here. Now what I want to do is review sketch

perspective because here we're learning constructions, remember

depends on our eye line.

I'm going to have to put down an eyeline first before I begin

to draw our box accurately because as we know in

perspective forms will converge to what's known as a vanishing

point. So let's say this imaginary line is my eye line

here. So I'm saying I'm roughly like looking smack in the

middle of our box in this case. So all of the the corners will

converge

to appoint known as the vanishing point.

Vanishing point, just call it VP, now you may be familiar with

this concept, so very basic concept in drawing but this is

what helps make our 3D form feel realistic. When we

converge to the vanishing point on our eye line this

also will tell the viewer because I'm not only paying

attention remember to our eye line, but the viewers as well.

So whoever looks at our drawing

will feel that they're in this position in 3D space. That's

what we're doing here. So that corner will also converge.

This corner will also converge.

And actually this point we'll also converge. Remember we want

to draw through,

treat it as if it's a transparent object like a piece

of glass.

Draw through. So this converges see the right vanishing point

or VP. These ends, these corners converge to the left BP.

You see that? Now we have something similar to

see that box drawing. Notice we can see the top plane of this

box. That means our eye level is above. Now

our eye level can be at the form and I'll show you what

that looks like real quick.

Same concept, eye level.

And let me just draw a couple of converging

lines here.

Sometimes I like to do this is to sketch a few

lines, not only helps me practice my dexterity drawing

straight lines remember

we had some exercises like that,

but now it gives me a choice as to how big or how

small I want my box because once I have these

converging lines, I can drop in some verticals

and just going to ghost those in. Remember always drawing through, in birth always drawing through

ghosting, practicing, rehearsing before we lay down the mark and

now look out how pretty my box is even though there's straight

lines drawn by hand. They look fairly okay.

And let me draw through. So this corner remember goes through.

Always want to think about drawing through when we're

beginning our 3D drawing. It's Ddrilling in our mind that there

is a backside.

This isn't just a shape. There's now a backside drawing

through, drawing through. So now we have our transparent form or

in this case our box.

Last our eye line can be below the box. Just going to draw a few

diagonals here just to

give me a rough estimate what my box could look like.

And then drop in a vertical, couple verticals, and now I have

an idea what my box form will be.

And then draw through,

draw through, from corner to the vanishing point,

you know, we don't have to be perfect notice - not perfect by any

means and I haven't used a ruler yet. That's why I always

recommend those exercises, right? Remember the exercises

where we learn, we get the muscle part of it down.

Okay so now we can see the under plate of our cube. And

I'm going to - I'm just going to add a little tone so you can

see what I'm talking about. See that we can see that. That

means our eye levels is below. We can see underneath the form our

eye level's below.

We can see through the form, roughly in the middle.

And this one is above and below we can see the top. So really

quick introduction into drawing a box form in basic perspective

using the eye line as your horizon line. Two vanishing

points in this case. This is also known as two point perspective.

as the 2D, the silhouette, also known as the contour.

Other ways you can think about it, shape,

contour,

silhouette. French word.

Basically means the outer edge

and we're going to start with our basic forms.

In this case as a shape it is a circle and notice the way I'm

drawing again, drawing with the whole body, drawing through,

practicing, ghosting, before I commit to a line.

Really helps to make better circles and to make our forms

feel more 3D and real that's the end goal. Next is the cube,

the box.

And the outer edge of the box,

contour, silhouette very simple.

If we just look at the box itself the contour in this form

in this flat 2D graphic shape, silhouette of the box, the outer

edge almost appears like another shape,

hexagon shape, notice that. And then finally the cylinder.

Cylinder,

interesting shape.

It's basically like the box here but curved at the end.

So very simple, very graphic.

Okay. Next we're going to do the 3D drawing, starting with

the box here. Now what I want to do is review sketch

perspective because here we're learning constructions, remember

depends on our eye line.

I'm going to have to put down an eyeline first before I begin

to draw our box accurately because as we know in

perspective forms will converge to what's known as a vanishing

point. So let's say this imaginary line is my eye line

here. So I'm saying I'm roughly like looking smack in the

middle of our box in this case. So all of the the corners will

converge

to appoint known as the vanishing point.

Vanishing point, just call it VP, now you may be familiar with

this concept, so very basic concept in drawing but this is

what helps make our 3D form feel realistic. When we

converge to the vanishing point on our eye line this

also will tell the viewer because I'm not only paying

attention remember to our eye line, but the viewers as well.

So whoever looks at our drawing

will feel that they're in this position in 3D space. That's

what we're doing here. So that corner will also converge.

This corner will also converge.

And actually this point we'll also converge. Remember we want

to draw through,

treat it as if it's a transparent object like a piece

of glass.

Draw through. So this converges see the right vanishing point

or VP. These ends, these corners converge to the left BP.

You see that? Now we have something similar to

see that box drawing. Notice we can see the top plane of this

box. That means our eye level is above. Now

our eye level can be at the form and I'll show you what

that looks like real quick.

Same concept, eye level.

And let me just draw a couple of converging

lines here.

Sometimes I like to do this is to sketch a few

lines, not only helps me practice my dexterity drawing

straight lines remember

we had some exercises like that,

but now it gives me a choice as to how big or how

small I want my box because once I have these

converging lines, I can drop in some verticals

and just going to ghost those in. Remember always drawing through, in birth always drawing through

ghosting, practicing, rehearsing before we lay down the mark and

now look out how pretty my box is even though there's straight

lines drawn by hand. They look fairly okay.

And let me draw through. So this corner remember goes through.

Always want to think about drawing through when we're

beginning our 3D drawing. It's Ddrilling in our mind that there

is a backside.

This isn't just a shape. There's now a backside drawing

through, drawing through. So now we have our transparent form or

in this case our box.

Last our eye line can be below the box. Just going to draw a few

diagonals here just to

give me a rough estimate what my box could look like.

And then drop in a vertical, couple verticals, and now I have

an idea what my box form will be.

And then draw through,

draw through, from corner to the vanishing point,

you know, we don't have to be perfect notice - not perfect by any

means and I haven't used a ruler yet. That's why I always

recommend those exercises, right? Remember the exercises

where we learn, we get the muscle part of it down.

Okay so now we can see the under plate of our cube. And

I'm going to - I'm just going to add a little tone so you can

see what I'm talking about. See that we can see that. That

means our eye levels is below. We can see underneath the form our

eye level's below.

We can see through the form, roughly in the middle.

And this one is above and below we can see the top. So really

quick introduction into drawing a box form in basic perspective

using the eye line as your horizon line. Two vanishing

points in this case. This is also known as two point perspective.

AUTO SCROLL

And of course, obviously the next thing,

going back 3D, we can take our conventional horizon line

and we can tilt it

so that we can create really interesting forms and basically

draw them from any angle and even from imagination, right,

that's what I'm doing here. I'm not really looking at a photo

of a box anymore, I'm working from imagination and that's

eventually what we will be doing in this lesson.

Really that's the goal here is to draw any 3D form from

imagination in any position, any angle, any the angle any

rotation of the our eye line here.

So notice drawing through, drawing through, drawing with the

arm, drawing through, drawing with the arm, back side, drawing

through. It's not just the front corner it's the back corner. So

I'm going to draw a point remember, point, point. That's

the back corner of that box. Drawing through.

Doing those exercises will really help at this stage to

help you get close. I mean, you can see here I'm not exactly

at the VP, the vanishing point, but I'm close. I'm close enough

with that I can start to compensate in my mind's eye

knowing what, you know, roughly what this shape should look

like.

At any point I could also get more accurate with rulers

and things, straight edges.

Makes you think in 3D. So now this is no longer flat

shape. It's a form

turns this way, goes from here, goes back.

Because we've drawn that backside. We've drawn that backside

so we created that feeling and I often

do that. I imagine that I'm crawling, actually riding

on a 3D object. I imagine like the form is here, like the

forms that we saw earlier I'm actually imagining that I'm like

physically riding on it and then turning my head, you see

that? Same kind of thinking, if I was going this way,

right, I would go, go here, and then

in my mind's eye, I don't literally do it, but that's the

way I'm thinking and that's the goal here and that's why I

again draw through, draw through, draw through. 12 through

going back 3D, we can take our conventional horizon line

and we can tilt it

so that we can create really interesting forms and basically

draw them from any angle and even from imagination, right,

that's what I'm doing here. I'm not really looking at a photo

of a box anymore, I'm working from imagination and that's

eventually what we will be doing in this lesson.

Really that's the goal here is to draw any 3D form from

imagination in any position, any angle, any the angle any

rotation of the our eye line here.

So notice drawing through, drawing through, drawing with the

arm, drawing through, drawing with the arm, back side, drawing

through. It's not just the front corner it's the back corner. So

I'm going to draw a point remember, point, point. That's

the back corner of that box. Drawing through.

Doing those exercises will really help at this stage to

help you get close. I mean, you can see here I'm not exactly

at the VP, the vanishing point, but I'm close. I'm close enough

with that I can start to compensate in my mind's eye

knowing what, you know, roughly what this shape should look

like.

At any point I could also get more accurate with rulers

and things, straight edges.

Makes you think in 3D. So now this is no longer flat

shape. It's a form

turns this way, goes from here, goes back.

Because we've drawn that backside. We've drawn that backside

so we created that feeling and I often

do that. I imagine that I'm crawling, actually riding

on a 3D object. I imagine like the form is here, like the

forms that we saw earlier I'm actually imagining that I'm like

physically riding on it and then turning my head, you see

that? Same kind of thinking, if I was going this way,

right, I would go, go here, and then

in my mind's eye, I don't literally do it, but that's the

way I'm thinking and that's the goal here and that's why I

again draw through, draw through, draw through. 12 through

AUTO SCROLL

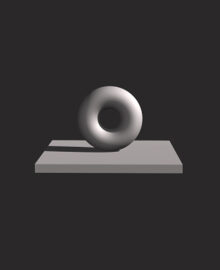

Now the next form is the cylinder and drawing the

cylinder in 3D is a little interesting because in a lot of

ways it's like the box, it has two straight edges. It also

has interesting idea known as the ellipse. Let's start with

our eye line again.

Drawing some

vanishing points here.

And what I'm going to do here is I'm drawing an ellipse

which is imagine in the center of the circle.

Imagine you cut

like an orange, you cut it off and then what you'll see in

perspective is what's known as an ellipse. That's what we're

doing here and I'll talk about ways that we can make our

ellipses more accurate.

A lot of ways you can think of them as boxes as well, see that?

Is it - there's also a middle. So what we want to do is imagine

the - let's say we'll take the bottom corner of this form.

We're drawing through, again drawing through, starting at the

front, drawing through, drawing through, making contact with the

sides because that's a corner again. The corner's most

imported when establishing the 2D. same with the top.

So what we want to do is we're going to cut this in half. So

from top to bottom.

Let's kind of draw an imaginary line through and I'll do the

same with the top.

Okay, let me get rid of this

so you can see better.

Prospective in a moment. And then what we're going to do is draw

an imaginary line that runs exactly down the middle of our

cylinder, basically cutting it into even halves, here the way to even halves here the way

we're looking at it and that point is exactly the middle of

the top and the bottom side of our cylinder.

And this is known as the center line.

Center line. This is important because this will help us draw

the cylinder from almost any angle. So for example

if I want to draw the cylinder - say here's my eyeline - I want

to try to draw the cylinder coming towards me like an arm or a

finger. Imagine your finger coming towards you, right,

finger's a cylinder like that. So I'm gonna draw vanishing point, and some dog banishing point, and

I'm going to draw

that is a center line. So how do we draw our cylinder around

this area.

Well I'm gonna start with a circle and

I'm going to imagine the point where

the center line is right in the center of the circle and notice

my circles not perfect, but it's okay because I